Tasfiah Rahman reports on the current provisions against domestic violence in Bangladesh, and suggests the need for reform.

During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the National Helpline Centre for Violence Against Women and Children in Dhaka, Bangladesh, received over 10,000 calls every day1. While domestic violence has been a major issue in Bangladesh for many years, the recent lockdown has coincided with a concerning increase in incidents of domestic violence

Domestic abuse breaches the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection Act) 2010 (DVPPA), the main statute for domestic violence in Bangladeshi law which states that domestic violence can take place physically, psychologically, sexually or economically against a woman or child by any family member.2

Domestic violence also breaches international legislation such as the Human Rights Act 1992 and the UN Conventions on the Rights of the Child 1990. However, it is clear that these acts do not go far enough to protect Bangladeshis from domestic abuse, which was especially evident during the recent crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic. This article will consider the protection that is available for men, women and child victims of domestic abuse in Bangladesh, and suggest ways in which the government could improve the current legislation.

Child victims of domestic violence

According to UNICEF, physical discipline is a ‘corporal punishment’ that refers to any punishment where physical and/or psychological force is used to cause any degree of pain or discomfort and to control children.3 Physical discipline is used across all levels of Bangladeshi society. In fact, 82.4% of children in Bangladesh between 1–14 years of age have experienced either physical or psychological abuse.4

The UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 consists of articles protecting the rights of parents, families and carers to raise a child in a way that respects their rights5; and to make sure that their child is protected from any type of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse or sexual exploitation while the child is living with their parents or in the care of anyone else6. In addition, the government must protect children from any form of sexual abuse7; must make sure that children are never tortured and never treated in a way that is cruel, inhuman or degrading8; and if a child has been the victim of abuse, the national government must make sure that the child is given the help to recover9. It is disappointing that the government in Bangladesh has still not complied with these sections of the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990.

While the schools in Bangladesh were closed due to the pandemic, children doing their school classes online had little escape from toxic home environments. A first step towards reducing physical punishment and abuse towards children would be to tackle its normalisation in Bangladesh. In addition, the government could take inspiration from the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 to incorporate its protections into the Bangladeshi legal system.

That’s not to say that there is no Bangladeshi legislation to protect children from abuse. The DVPPA gives victims of domestic violence (including children), or someone acting on their behalf (for example, an enforcement officer or a service provider), the right to apply for a remedy in any court in Bangladesh.10 The Children Act 2013 paves a similar pathway via the Child Welfare Board, which helps protect children who are living under unsafe conditions, through children’s courts, bail provisions and legal representation.11 However, in order to reach these services, the government should find ways to advertise helplines such as the Child Helpline. This helpline was created for children under 18, as a way for them to report domestic abuse cases immediately to the nearest police stations.

Female victims of domestic violence

The Covid-19 lockdown has exacerbated domestic violence against women around the world due to increases in household tension as a result of stay-at-home orders, economic fears, and stress about the virus.12 The Bangladesh human rights group, Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), has reported that at least 235 women were murdered by their husband or his family in just the first nine months of 2020.13 Due to societal pressures and fear of judgement, women of all classes often remain silent despite hostile home environments, as they are scared to take any action.14

The Human Rights Act 1998 plays a vital role in protecting women against domestic abuse. Fundamental human rights include the right to life15, the right not to be tortured or treated in an inhuman and degrading way16, the right to respect for private and family life17 (including the right to physical and psychological integrity), the right to education18, and the right not to be discriminated against19. All of these can be infringed when a woman is the victim of domestic abuse.

According to the prominent Bangladesh human rights group, Odhikar, between January 2001 and December 2019, over 3,300 women and girls were murdered in the country over dowry disputes.20 This is still an issue despite the case of Nure Alam v State, after which it was made punishable to demand a dowry under section 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act 1980.21

Girls who marry under 18 years of age are more likely to be victims of domestic violence.22 Bangladesh is among the top-10 countries in the world for child marriage. It is eighth from the bottom in South Asia, according to a UN report that said Bangladesh has a 51% child marriage rate.23 Difficult financial situations caused by the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have made parents less willing to keep their unmarried daughters at home over the last year as they can’t afford further education. The international development organisation BRAC, which is based in Bangladesh, stated that it had prevented 670 child marriages in 2019 and 1,091 in 2020 through persuasion and educational efforts. However, there were still 167 additional attempts at child marriage in Bangladesh in 2019 and 292 in 2020.24

The law states that the minimum legal age for females to get married is 18 years, while for males it is 21 years, under the Child Marriage Restraint Act, 2017. Nevertheless, in many areas of Bangladesh, people have no knowledge of the legislation against child marriage.25 This has made preventing underage marriages in Bangladesh a serious challenge.

Victims can take actions on their abusers in Bangladesh via remedies and other compensation. The punishment for rape is the same under s 9, Prevention of Women and Children Repression Bill 200026 and the Penal Code of 1860, s.376 where it says “whoever commits rape shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to 10 years, and shall also be liable to fine.”27 Even though domestic abusers are at risk of imprisonment, life sentences and fines, it is worth remembering that domestic abuse can have a lifelong effect on victims.

Under the DVPPA, a domestic violence offence shall be punished with imprisonment which may extend to 6 months or a fine of 10 thousand Taka or both28. It is arguable that this punishment is relatively short and is not a sufficient penalty.

Male victims of domestic violence

In 2020, the Bangladesh Men’s Rights Foundation (BMRF) stated that around 80% of men in the country face mental abuse from their spouses.29 BMRF also disclosed that “the victims do not want to reveal their identities for fear of social embarrassment.”30 This is in part due to the patriarchal society that exists in Bangladesh, where restrictive gender roles endure and where men are expected to dominate women.

Almost all the domestic abuse-related statutes in Bangladesh have thresholds for women and child victims, but there is very little protection for men victims. Although domestic violence is not as prevalent against men as against women and children in Bangladesh, this means that there is very little support for adult males’ protection from domestic abuse. It is arguable that the Bangladesh government should be open to taking further action into incorporating sections or articles, especially in the DVPPA, which can provide male victims with equal support to women victims. This could also have the effect of encouraging more male victims to come forward.

Discrimination based on sex is prohibited under human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which under common article 3 provides the rights to equality between men and women in the enjoyment of all rights.31 However, this international legislation is not applied in the domestic abuse laws in Bangladesh. As they are not protected under the legislation, men and boys can have a hard time proving that they have been a victim of domestic abuse to the courts.

Conclusion

Domestic violence is a serious issue in Bangladesh, and one that has been worsened by the stay-at-home conditions of the pandemic. Women, children and men can all fall victim to domestic abuse, but while there are statutes in place in Bangladesh to support women and children, men are not always afforded the same protection. It is also obvious that there are loopholes and shortcomings as to the efficient implementation and adequacy of those laws that do exist, which became particularly clear during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is important that the government learns to implement more facets of the international Human Rights Act in order to protect victims and prevent abusers.

[1] Hasina, ‘National Helpline Centre for Violence against Women and Children’ (National Helpline Centre for Violence against Women and Children, 2 November 2010) <http://nhc.gov.bd/> accessed 10 March 2021

[2] Domestic Violence Act (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010, s.3

[3] Ortiz-Ospina E and Roser M, “Violence against Children and Children’s Rights” (Our World in DataOctober 24, 2017) <https://ourworldindata.org/violence-against-rights-for-children> accessed May 16, 2021

[4] Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and Unicef Bangladesh. Child well-being survey in urban areas of Bangladesh, key results. Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2016. <https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/CWS_in_urban_areas_Key_Findings_Report_Final_04122016.pdf> accessed June 23 2021

[5] Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 , Article 5

[6] Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 , Article 19

[7] Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990, Article 34

[8] Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990, Article 37

[9] Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990, Article 39

[10] Domestic Violence Act 2010, Chapter 4, s (20) (3)

[11] “Towards Justice for Children” (UNICEF Bangladesh) <https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/raising-awareness-child-rights/towards-justice-children> accessed March 9, 2021

[12] ‘Domestic violence and abuse: safeguarding during the Covid-19 pandemic’(Social Care Institute for Excellence, 31 March 2021) < https://www.scie.org.uk/care-providers/coronavirus-covid-19/safeguarding/domestic-violence-abuse> Accessed 23 June 2021

[13] “‘I Sleep in My Own Deathbed’” (Human Rights WatchNovember 12, 2020) <https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/10/29/i-sleep-my-own-deathbed/violence-against-women-and-girls-bangladesh-barriers> accessed June 23, 2021

[14] Dr Nasrin Rahman, “Preventing Domestic Violence against Women” (The Daily Star November 23, 2020) <https://www.thedailystar.net/law-our-rights/news/preventing-domestic-violence-against-women-2000193> accessed March 9, 2021

[15] Human Rights Act 1998, Sch 1, Part 1, Article 2

[16] Human Rights Act 1998, Part 1, Article 3

[17] Human Rights Act 1998, Part 1, Article 8

[18] Human Rights Act 1998,Part 2, Article 2

[19] Human Rights Act 1998,Part 2, Article 2

[20] “‘I Sleep in My Own Deathbed’” (Human Rights WatchNovember 12, 2020) <https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/10/29/i-sleep-my-own-deathbed/violence-against-women-and-girls-bangladesh-barriers> accessed June 23, 2021

[21] Dowry Prohibition Act 1980, s4

[22] ‘Child Marriage’ (Unicef) https://www.unicef.org/protection/child-marriage Accessed 23 June

[23] Sakib N, “Bangladesh: Child Marriage Rises Manifold in Pandemic” (Life, Asia, PacificMarch 22, 2021) <https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/bangladesh-child-marriage-rises-manifold-in-pandemic/2184001> accessed June 23, 2021

[24] Sakib N, “Bangladesh: Child Marriage Rises Manifold in Pandemic” (Life, Asia, PacificMarch 22, 2021) <https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/bangladesh-child-marriage-rises-manifold-in-pandemic/2184001> accessed June 23, 2021

[25] Reza S, “Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS)” (2021) 26 Domestic Violence against Women in the Time of Pandemic in Bangladesh <www.iosrjournals.org> accessed June 7, 2021

[26] Prevention of Women and Children Repression Bill 2000, s.9

[27] The Penal Code of 1860, s.376

[28] Domestic Violence Act 2010, Chapter 6

[29] Jahangir, ‘Bangladesh: Male victims of domestic violence demand gender-neutral laws’ (DWCOM, 20 November 2020) <https://www.dw.com/en/bangladesh-domestic-abuse-male-victims/> accessed 10 March 2021

[30] Jahangir, ‘Bangladesh: Male victims of domestic violence demand gender-neutral laws’ (DWCOM, 20 November 2020) <https://www.dw.com/en/bangladesh-domestic-abuse-male-victims/> accessed 10 March 2021

[31] Human Rights and Gender – United Nations and the Rule of Law” (United Nations) <https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/thematic-areas/human-rights-and-gender/> accessed June 7, 2021

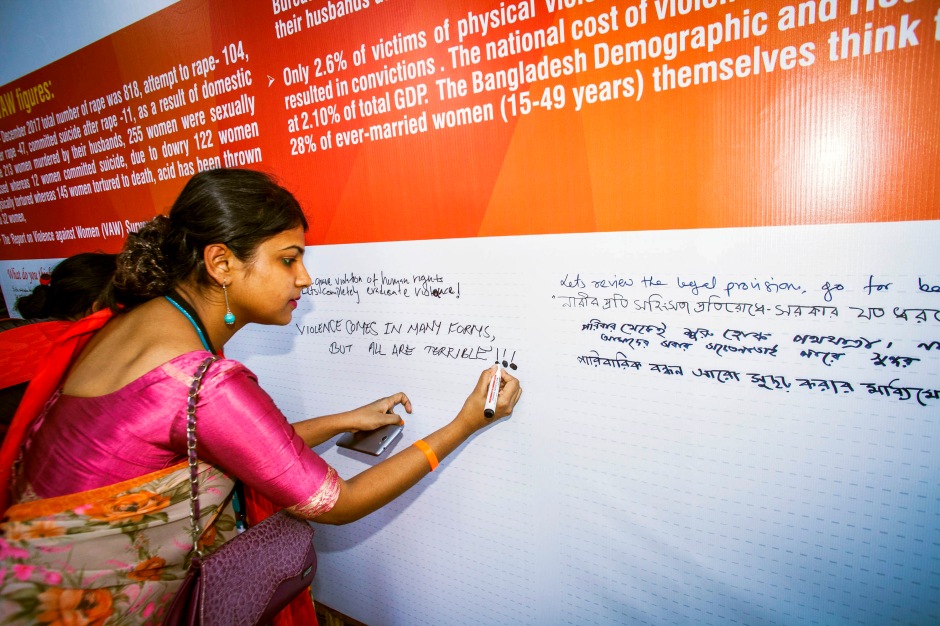

Image credit: A woman writes on a pledge board at Orange the World 2018 in Bangladesh, marking 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence © UN Women/Flickr

Disclaimer: The BPP Human Rights blog, and all pieces posted on the blog, are written and edited exclusively by the student body. No publication or opinion contained within is representative of the values or beliefs held by BPP University or the Apollo Education Group. The views expressed are solely that of the author and are in no way supported or endorsed by BPP University, The Apollo Education Group or any members of staff.